Collaboration with Steven Harrison & Spencer Ferris. Consultants: Maho Ishiguro and Darsono (Emory University).

A PDF version of the SMPC 2024 poster is available to see here.

Any comments or questions can be sent to stefanie.acevedo[a]uconn.edu

Abstract

(As presented at SMPC 2024 Conference)

We investigate how athletic and musical training affects synchronization during Javanese Gamelan performance. Gamelan A) represents a complex social coordination phenomenon across complexly nested rhythms; B) has mallet sizes that generate physical constraints, affecting movement organization (Russell & Sternad 2001; Manning et al. 2017); and C) contains melodic (balungan) beat IOIs between 400-9000 ms with rapid tempo changes (Brinner, 1995). Coordination with IOIs over 2000ms has not been studied (Repp 2005; Torre & Wagenmakers 2009; Repp & Su 2013). Anecdotal correspondence suggests heightened ability of athletes during gamelan performance. There is little research on the effect of athletic ability on musical performance (Miura et al. 2013, Janzen et al. 2014, Chatzopoulos 2019, Jin et al. 2019), which we test here.

After learning an 8-beat melody, subjects synchronize to recorded stimuli (protocol: Large et al. 2002; Pfordresher 2005) on a xylophone-like saron. Task conditions (simulating gamelan vs. Western music tendencies) include A) isochronous IOIs (375ms–2000ms); B) changing tempi (±30% to ±100% of initial tempo); and C) synchronization to two-layer (melody, kendhang drum) versus three-layer (subdividing peking) textures. Motion capture and EMG measures subject groups [non-musician/non-athlete controls, Western percussionists (musicians), and basketball/tennis players (athletes)] for 1) accuracy (beat-tap asynchronies), 2) kinematics (embodied timing/anticipatory movements), and 3) activation patterns (muscle pair co-contractions). Recent tapping synchronization (Scheurich et al. 2020) and rhythmic athletic (Katsuhara et al., 2010) studies suggest appropriate power at group sizes of n=30.

We discuss results based on the following hypotheses: Athletes should be more accurate than non-musicians since motor training influences timing tasks (Huff 1972; Zachopoulou et al. 2000; Katsuhara et al. 2010) and there is increased muscle synergy efficiency with physical activity and during mallet striking motions (Gribble et al. 2003; de Fonseca et al. 2006; Ford et al. 2008). Due to movement-enhanced rhythmicity (i.e. Manning et al. 2020), musicians and athletes should show embodied timing strategies that vary by stimuli tempo (Bardy et al. 2002; Toiviainen et al. 2010; Creath et al. 2015; Burger et al. 2018).

Musical Examples

- Balungan = played on saron (same timbre and octave as participant’s instrument)

- Kendhang = lead drummer (modified from standard gamelan patterns)

- Peking (aka saron panerus) = 1st subdivision layer (octave above participant’s instrument)

Isochronous examples:

- 60 bpm (1000 ms IOI) –

Examples recorded in an ecologically valid manner (which creates noise artifacts from the instrument’s timbre and internal reverberation) and edited with Pro Tools (including beat detection/quantization and filtering/compression).

Sample Gamelan Texture

The metrical grids below show two Irama types in the piece Moncèr (listen here).

The Balungan

The balungan (main melody) is performed by multiple instruments (slenthem, saron barung, and saron demung). The Peking (aka Saron Panera’s) and Bonang Barung perform the first subdivision level. Bonang Panerus usually plays the second subdivision level (not played in this example.

The original notation shows the melody (balungan) beat.

(The highlighted portion is dissected below)

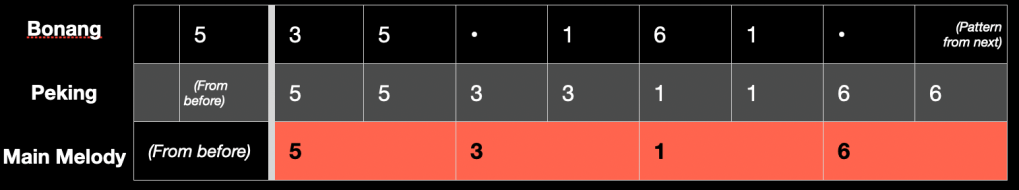

Irama Tanggung

Ratio of two peking subdivisions per Balungan beat.

Note the bonang does not only play subdivisions but also staggers its entrance.

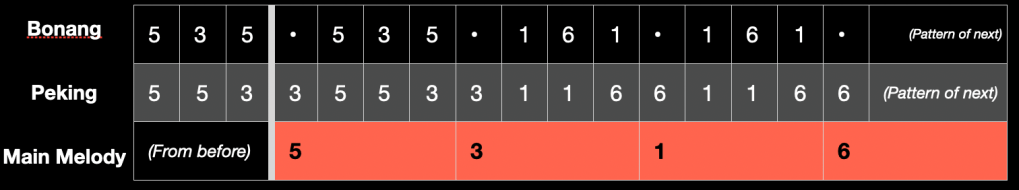

Irama Dadi

Ratio of four peking subdivisions per Balungan beat.

Note how the bonang and peking double their rhythm and stagger their entrances prior to the onset of the balungan beat.

Works Cited

Bardy, B.G., Oullier, O., Bootsma, R.J., & Stoffregen, T.A. (2002). Dynamics of human postural transitions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 28(3), 499.

Brinner, B. (1995). Knowing Music, Making Music: Javanese Gamelan and the Theory of Musical Competence and Interaction. University of Chicago Press.

Burger, B., London, J., Thompson, M.R., & Toiviainen, P. (2018). Synchronization to metrical levels in music depends on low-frequency spectral components and tempo. Psychological Research, 82(6), 1195-1211.

Chatzopoulos, D. (2019). Effects of ballet training on proprioception, balance, and rhythmic synchronization of young children. Journal of Exercise Physiology, 22(2).

Creath, R., Kiemel, T., Horak, F., Peterka, R., & Jeka, J. (2005). A unified view of quiet and perturbed stance: Simultaneous co-existing excitable modes. Neuroscience Letters, 377(2), 75-80.

da Fonseca, S.T., Vaz, D.V., de Aquino, C.F., & Brício, R.S. (2006). Muscular co-contraction during walking and landing from a jump: Comparison between genders and influence of activity level. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 16(3), 273-280.

De Bruyn, L., Leman, M., & Moelants, D. (2008). Quantifying children’s embodiment of musical rhythm in individual and group settings. In K. Miyazaki, Y. Hiraga, M. Adachi, Y. Nakajima, & M. Tsuzaki (Eds.), Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Music Perception and Cognition (CD-ROM (pp. 662–667). Adelaide, Australia: Causal Productions.

Drake, C., & Botte, M.-C. (1993). Tempo sensitivity in auditory sequences: Evidence for a multiple-look model. Perception & Psychophysics, 54(3), 277–286.

Drake, C., Jones, M.R., & Baruch, C. (2000). The development of rhythmic attending in auditory sequences: Attunement, referent period, focal attending. Cognition, 77(3), 251–288.

Ford, K.R., Van den Bogert, J., Myer, G.D., Shapiro, R., & Hewett, T.E. (2008). The effects of age and skill level on knee musculature co-contraction during functional activities: A systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 42(7), 561-566.

Fujii, S., Kudo, K., Shinya, M., Ohtsuki, T., & Oda, S. (2009). Wrist muscle activity during rapid unimanual tapping with a drumstick in drummers and nondrummers. Motor Control, 13(3), 237-250.

Geringer, J.M., & Madsen, C.K. (1984). Pitch and tempo discrimination in recorded orchestral music among musicians and nonmusicians. Journal of Research in Music Education, 32(3), 195–204.

Geringer, J.M., & Madsen, C.K. (2003). Gradual tempo change and aesthetic responses of music majors. International Journal of Music Education, 40(1), 3–15.

Graber, E., & Fujioka, T. (2020). Induced beta power modulations during isochronous auditory beats reflect intentional anticipation before gradual tempo changes. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 4207.

Gribble, P.L., Mullin, L.I., Cothros, N., & Mattar, A. (2003). Role of cocontraction in arm movement accuracy. Journal of Neurophysiology, 89(5), 2396-2405.

Huff, J. (1972). Auditory and visual perception of rhythm by performers skilled in selected motor activities. Research Quarterly: American Association for Health, Physical Education and Recreation, 43(2), 197–207.

Janzen, T. B., Thompson, W.F., Ammirante, P. & Ranvaud, R. (2014). Timing skills and expertise: Discrete and continuous timed movements among musicians and athletes. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1482.

Jin, X., Wang, B., Lu, Y., Chen, J., & Zhou, C. (2019). Does dance training influence beat sensorimotor synchronization? Differences in finger-tapping sensorimotor synchronization between competitive ballroom dancers and nondancers. Experimental Brain Research, 237(3), 743–753.

Katsuhara, Y., Fujii, S., Kametani, R., & Oda, S. (2010). Spatiotemporal characteristics of rhythmic, stationary basketball bouncing in skilled and unskilled players. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 110(2), 469–478.

Kuhn, T.L. (1974). Discrimination of modulated beat tempo by professional musicians. Journal of Research in Music Education, 22(4), 270–277.

Lindsay, J. (1992). Javanese Gamelan: Traditional Orchestra of Indonesia. Oxford University Press.

London, J. (2012). Hearing in Time (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Madison, G., & Merker, B. (2002). On the limits of anisochrony in pulse attribution. Psychological Research, 66(3), 201–207.

Manning, F.C., Harris, J., & Schutz, M. (2017). Temporal prediction abilities are mediated by motor effector and rhythmic expertise. Experimental Brain Research, 235(3), 861–871.

Manning, F.C., & Schutz, M. (2016). Trained to keep a beat: movement-related enhancements to timing perception in percussionists and non-percussionists. Psychological Research, 80(4), 532–542.

Manning, F., & Schutz, M. (2013). “Moving to the beat” improves timing perception. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 20(6), 1133–1139.

Manning, F.C., Siminoski, A., & Schutz, M. (2020). Exploring the effects of effectors: finger synchronization aids rhythm perception similarly in both pianists and non-pianists. Music Perception 37(3): 196–207.

Martens, P.A. (2011). The ambiguous tactus: Tempo, subdivision benefit, and three listener strategies. Music Perception, 28(5), 433–448.

Martopangrawit, R.L. (1984). Catatan-Catatan Pengetahuan Karawitan [Notes on Knowledge about Gamelan Music]. In J. Becker & A. H. Feinstein (Eds.), & M. F. Hatch (Trans.), Karawitan: Sources Readings in Javanese Gamelan and Vocal Music (pp. 123–244). University of Michigan Press. Original work published 1972.

Miura, A., Kudo, K., Ohtsuki, T., Kanehisa, H., & Nakazawa, K. (2013). Relationship between muscle cocontraction and proficiency in whole-body sensorimotor synchronization: A comparison study of street dancers and nondancers. Motor Control, 17(1), 18-33.

Moelants, D. (2002). Preferred tempo reconsidered. In C.J. Stevens, D.K. Burnham, G. McPherson, E. Schubert, & J. Renwick (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Music Perception and Cognition. Causal Productions.

Moelants, D. (2003). Dance, music, movement, and tempo preferences. In R. Kopiez, A. C. Lehmann, I. Wolther, & C. Wolf (Eds.), Proceedings of the 5th Triennial ESCOM Conference (pp. 649–652). Hanover University of Music and Drama.

Pecenka, N., Engel, A., & Keller, P.E. (2013). Neural correlates of auditory temporal predictions during sensorimotor synchronization. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 380.

Pecenka, N., & Keller, P.E. (2011). The role of temporal prediction abilities in interpersonal sensorimotor synchronization. Experimental Brain Research, 211(3–4), 505–515.

Pfordresher, P., & Palmer, C. (2002). Effects of delayed auditory feedback on timing of music performance. Psychological Research, 66(1), 71–79.

Repp, B.H. (2000). The Timing Implications of Musical Structures. In D. Greer (Ed.), Musicology and Sister Disciplines: Past, Present, Future (pp. 60–70). Oxford University Press.

Repp, B.H. (2005). Sensorimotor synchronization: A review of the tapping literature. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 12(6), 969–992.

Repp, B.H., & Su, Y.H. (2013). Sensorimotor synchronization: A review of recent research (2006–2012). Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 20(3), 403–452.

Russell, D.M., & Sternad, D. (2001). Sinusoidal visuomotor tracking: Intermittent servo-control or coupled oscillations? Journal of Motor Behavior, 33(4), 329-349.

Schulze, H.H., Cordes, A., & Vorberg, D. (2005). Keeping synchrony while tempo Changes: Accelerando and ritardando. Music Perception, 22(3), 461–477.

Sumarsam. (2023). Introduction, Theory, and Analysis: Javanese Gamelan. Self-published manuscript. http://sumarsam.faculty.wesleyan.edu/files/2023/01/INTRO_THEORY_ANALYSIS-.pdf

Toiviainen, P., Luck, G., & Thompson, M. (2010). Embodied meter: Hierarchical eigenmodes in music-induced movement. Music Perception, 28(1), 59–70.

Torre, K., & Wagenmakers, E. J. (2009). Theories and models for 1/fβ noise in human movement science. Human Movement Science, 28(3), 297-318.

Van der Steen, M.C., Jacoby, N., Fairhurst, M.T., & Keller, P.E. (2015). Sensorimotor synchronization with tempo-changing auditory sequences: Modeling temporal adaptation and anticipation. Brain Research, 1626, 66–87.

Verrel, J., Pologe, S., Manselle, W., Lindenberger, U., & Woollacott, M. (2013). Exploiting biomechanical degrees of freedom for fast and accurate changes in movement direction: Coordination underlying quick bow reversals during continuous cello bowing. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 157.

Wong, J., Wilson, E.T., Malfait, N., & Gribble, P.L. (2009). Limb stiffness is modulated with spatial accuracy requirements during movement in the absence of destabilizing forces. Journal of Neurophysiology, 101(3), 1542-1549.

Zachopoulou, E., Mantis, K., Serbezis, V., Teodosiou, A., & Papadimitriou, K. (2000). Differentiation of parameters for rhythmic ability among young tennis players, basketball players and swimmers. European Journal of Physical Education, 5(2), 220–230.